Inflation, credit, and crisis: a reconception

Justin Aukema

21 June 2020

For Marxists, crisis is a problem of overaccumulation. This basically means that capitalism always attempts to create more than there is actually need or demand for. This is in fact obvious when one considers how capitalism works in general. Its goal is simply the accumulation of more capital. But to do this, it has to constantly produce more: more products, more value, more growth, etc. In other words, it always has to create surplus value. We can also think about this simply as the need to constantly create profits. Think about it this way. A limited number of people have a limited amount of needs. These needs are generally a known variable. Once they are met then there is no more need or demand for anything more. Of course, some surplus must always be created. But this surplus only needs to be enough to replace the yearly wear and tear of the means of production (tools, raw materials etc.); to accommodate for population shifts; and to satisfy the needs of those who can't work such as children and the elderly etc. There is not technically any need to produce above and beyond this speaking purely theoretically. But capitalism cannot be satisfied with this. It has to constantly produce more, a surplus over and above what is actually needed or demanded. This surplus itself is the origin of wealth and capital accumulation. Without this, capitalism would largely cease to be!

But where does this extra surplus value go? That is the age-old question. And it was only answered by Marx. Marx determined that the portion of surplus value goes back into the production process to increase the overall output. That is to say, it is reinvested back into the production process. He determined the general formula of value as follows:

Value = constant capital + (variable capital + surplus value); or, c + v + s

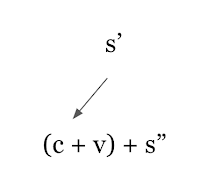

Now, the portion of s’ is reinvested back into the production process, specifically to increase the amount of c and v. A portion is used to maintain the wear and tear of tools and machines. But a portion can also be used to upgrade or expand machinery if available. Moreover, a portion can be reinvested in v, which is the cost of labor, or that is, workers’ wages. This may be necessary, for example, when hiring more workers etc. along with expanded production. It could also be used for wage raises. But in this case, the organic composition of capital and the rate of surplus value must always be higher than v. Put simply, this means that the rate of “productivity” etc. must exceed the amount (re)invested in wages if a constant surplus is to be maintained. The figure for this simple reproduction of capital, the basis for capital accumulation, is as follows:

This is just simple reproduction. There is also enlarged reproduction of capital. Simply put, this means that total social capital increases and accumulates. The significance of this is that a surplus must always be maintained and then reinvested somewhere. The cycle of accumulation never ceases because, again, if it did so, it would also cease to be capitalism.

Rosa Luxemburg dealt in detail with capital accumulation. She wanted to know what happened to the extra surplus, the s, since it always exceeded demand. Who were the extra consumers and where did they come from? Her basic answer was that capitalism always needs to expand to find new markets, new forms of commodification, and to bring previously non-commodified or non-capitalistic goods etc. into the market. This could be done through colonization, warfare, privatizations, or other means. This would create new avenues for capital expansion. It would allow not only new places for investment, but also provide new access to raw materials and labor power. Both of these could be used to lower the costs of c (which includes raw materials) and v (labor power) and thus increase the rate and amount of s.

But there is a problem. Capital accumulation inherently leads to crisis and especially crisis of overaccumulation. This manifests itself in warfare, inflation, etc. First, there is the crisis of overaccumulation capital, or s, itself. When it runs into limits, it seeks to overcome them through forcefully creating new markets etc. Second, there is the crisis caused by the increasing organic composition of capital, or the ratio of c:v. As the production process becomes further mechanized, the costs of c become higher. At the same time, there is less need for large numbers of workers, so the cost of v gets lower. However, this results in a contradiction. This is because only workers’ labor power can create new surplus value. Machines and tools by themselves cannot create this. Capitalism can try to overcome this, again, by creating new markets and thus obtaining demand for more labor.

But what happens when it can’t? What happens in a low growth scenario and when capitalism has largely run out of places to expand into? Then there is a crisis of value creation. In this scenario, masses of workers are either out of work or working precarious jobs. They themselves are not creating much value. But the cost of goods and raw materials is expensive due to increased production costs and costs of running expensive machinery etc. There is also high demand for many of these goods, especially essential goods such as food, housing, and clothing. When people’s wages are no longer enough to cover the cost of living, such as for example purchasing a house, and capitalism can no longer create new value to compensate for this, then the use of credit and finance will inevitably expand. That is to say, for example, more people will take out loans to buy major purchases like homes and cars etc, and even microloans to purchase basic necessities.

The explosion of credit and finance therefore is a direct response to the crisis of value creation and capital accumulation and is in direct inverse proportion to the amount of new value creation. The overall scenario can be envisioned as follows:

Growth rate here is bourgeois economics lingo but what I actually mean by it is the rate of surplus value, or the rate/amount of new value creation. When this is high, there will be little need for credit and finance schemes because, on the business side there is already enough rate of profit and surplus value to compensate for this, and on the consumer side, wages are either high enough to cover costs or costs and wages alike are both low in the first place. But as the amount of new value being created goes down, capitalists will need to cover their costs and obtain their profits through other means (credit) while consumers, too, will rely on credit to buy their goods.

This relates to inflation and deflation as well. High rates of profit and value creation are often linked to labor intensive and highly competitive commodity production scenarios where the cost of labor, machinery, and commodities are all very low. With little finance in the mix, this means there is generally a trend toward deflation resulting from a race-to-the-bottom commodity competition. But as value declines and credit expands, high demand, inability to purchase with anything other than credit, and high production costs from high constant capital, c, levels means that the price of basic goods will also go up. The capitalist must realize his surplus value through the completion of sale and compensate his costs and his hungry pockets somehow.

The overall element of crisis here can be explained simply as this: when credit increases and value creation decreases, there is more likelihood of crisis. This is obvious because credit itself is simply a promise of payment. But as value creation goes down there is actually less and less likelihood of that payment occurring in the first place. More and more people may be buying expensive homes etc. on credit, but if they are facing less stable income or decreased wages etc. then their ability to repay is threatened. In sum, this model confirms Marx’s thesis of crisis as the result of an inability of repayment.

Japan’s situation

Now, you might ask how Japan fits into this picture. Don’t they have massive deflation? What’s the deal? Well, actually Japan also fits this model perfectly. But it is not possible to understand Japan’s situation using traditional models for gauging inflation such as monetary theory or theories involving interest rates. After all, Japan has incredibly low interest rates and pioneered unconventional monetary policy through quantitative easing. So according to mainstream theory all of the factors are there. Except for the inflation.

Or so it seems. The basic point is that Japan uses massive amounts of credit and has very little value creation. Government debt has ballooned to 200x the country’s GDP. This is why interest rates must be so low: because otherwise the government couldn’t pay back the interest on all of its bonds. At the same time wages in Japan are incredibly depressed. This itself is a result of capital accumulation wherein the ratio of c:v steadily rises as explained above. This scenario increases the industrial reserve army of labor including the precariously employed who now make up 40% Japan’s workforce. It can also lead to increased production costs but also less ability to purchase basic goods. This gap thus must be made up for with credit.

As is indeed the case. The actual price of essential goods such as homes, for instance, is well beyond people’s actual purchasing power. Homes are especially important because they are in fact the inflation sink that rising costs are buried into. The expansion of credit through home loans makes up for this gap and with low interest rates it enables people to obtain their bare essentials while simultaneously maintaining the fiction that runaway inflation isn’t happening.

But this fiction is getting increasingly hard to maintain. This is because Japan also suffers a major lack of value creation. The country has experienced little to no new growth for the past three decades. Attempts to compensate for this have mainly been achieved by Japanese corporations moving production overseas to cut labor costs to their bare minimum. This also reduces some commodity costs in Japan which is itself necessary since Japanese workers’ own wages are insufficient to buy anything other than super cheap goods. This method of value creation may increase the rate of surplus value and capitalists profits. But ultimately it does not benefit Japanese workers since the ability to purchase some cheap commodities is both a direct cause of and consequence of the cheapened value of labor both at home and abroad. Moreover, this counteracting influence itself is still subject to the same crisis of overaccumulation wherein the organic composition of capital, c:v, rises as production is mechanized and “productivity” raised etc. Thus even Japan will not be able to avoid the pitfall of rising prices versus increasing inability to purchase commodities.

Indeed, this is what we have already been seeing for some time. Much data on Japan looks at year on year CPI index to arrive at the conclusion that Japan has a deflationary tendency. This is partly supported by the further “evidence” of low interest rates and low wages. It is generally recognized even among bourgeois economists that Japan’s low wages are a problem. But those same economists get confused when it comes to demand. Instead of wages stimulating demand, they frequently say that prices stimulate demand. But this is a logical conundrum since wages and prices are intimately connected (although not the only factor, obviously). One problem is that wages and prices both can still be low but can also rise relatively in the long term. This is precisely what the data reveals. Ueno Takeshi from the NLI Research Institute compiled data on OECD countries from 1995 to 2020 comparing price rises with wages. This shows that while in other countries wages have risen faster than prices, in Japan the opposite has been true: wages have risen more slowly relative to prices.

Figure 2: The rise in wages vs rise in prices, 1995 - 2020; Originally printed in the Tokyo Shimbun

This creates a major problem that is not explainable with many other traditional theories. Furthermore, it complicates the assumption that Japan is experiencing long term deflation. Instead, the truth is more complicated. There is a tendency toward overall inflation in the global market as evidenced by rising prices. Even Japan is not immune from this. It imports key raw materials etc. upon which whole domestic industries depend (e.g. for house building etc.). Moreover, rising labor costs abroad may also complicate Japan’s hitherto business model of exploiting cheap foreign labor. Thus it is more accurate to say that the biggest deflation Japan is experiencing is only in the realm of v, of workers’ wages. This is a direct consequence of the cheapening of labor due to the capital accumulation process. It is illustrated by my model and the models of other Marxist scholars explained here. But most bourgeois economics itself either does not recognize or obscures this facet.

Incidentally, we can add one more statement here. This is the reason for Japan’s low wages in the first place. Most of this relates to the overall cheapening of labor through the capital accumulation process; that is to say, the shift in the organic composition of capital away from v. Obviously this will lead to problems of value creation and crisis. But even from a standard economics perspective there are other clear reasons. One benefit for Japanese companies is that lower wages, along with a weak yen etc., make Japanese exports more beneficial in the global market. Japan’s exports as a percentage of its GDP have risen greatly since the 1970s. Actually, there was a break in this after the 1985 Plaza Accords and a rise in the price of the yen. But this has rebounded from the mid-1990s to reach its present levels of over 18%.

Because of Japan’s advanced monopoly capital and its high organic composition of capital, it actually costs a lot to make high tech goods in Japan. So what can Japanese companies do? Naturally, the only remaining routes available to them are A) to reduce the costs of constant capital by obtaining cheaper raw material imports; B) obtaining cheaper labor costs abroad; and C) cheapening labor at home through mechanization, productivity advances etc. A) is not really an option anymore, so only B) and C) remain. A reliance on the export market and low wages domestically means that Japanese corporations seek to realize the value of their products mainly abroad in richer countries rather than at home. In other words, they target mostly foreign consumers in America, China, Europe etc. rather than in Japan.

Now, positing solutions to this problem is beyond the scope of this essay. The aim was rather only to present a new way of thinking about inflation and deflation. One major lesson we can learn from this in the case of Japan is that it is possible to have a situation that looks like deflation but where there is actual inflation that is simply hidden. Interest rates and monetary supply etc., the main indicators of inflation in mainstream economics, though, cannot explain this facet entirely. Instead, as I have suggested, Marxist crisis theory relating to the organic composition of capital and capital accumulation offers a much clearer picture. Only this, in other words, explains why it is possible to have both declining wages and rising prices. Based on this, the obvious conclusion that many left-leaning economists draw, therefore, is to raise wages which they think will stimulate domestic demand. Of course, raising wages is necessary for the betterment of the global working class. Yet it is also not totally incompatible with the capitalist model of growth and accumulation. Indeed, capitalists must raise wages to a certain extent (enough to buy basic necessities) to support the reproduction of the working class. In addition, capitalists can generally raise wages insofar as this rise itself doesn't threaten the portion of surplus value, s, being extracted. This can be offset with rises in and exploitation or so-called productivity. Or, another option available to capitalists is to continue to depress wages and instead to make up for rising prices with the expansion of credit. Finally, another more extreme option would be to resort to other measures such as locking down a portion of the global working class in order to shut off or to regulate global supply and demand. This is especially important in times of crisis when a large portion of the working class becomes redundant (surplus population); in times of looming hyperinflation due to ballooning prices and an inability to sell these goods; or when wage rises threaten the capitalists’ portion of surplus value. Indeed, some have argued that this was part of the purpose of the global Covid lockdowns in the first place.

21 June 2020

For Marxists, crisis is a problem of overaccumulation. This basically means that capitalism always attempts to create more than there is actually need or demand for. This is in fact obvious when one considers how capitalism works in general. Its goal is simply the accumulation of more capital. But to do this, it has to constantly produce more: more products, more value, more growth, etc. In other words, it always has to create surplus value. We can also think about this simply as the need to constantly create profits. Think about it this way. A limited number of people have a limited amount of needs. These needs are generally a known variable. Once they are met then there is no more need or demand for anything more. Of course, some surplus must always be created. But this surplus only needs to be enough to replace the yearly wear and tear of the means of production (tools, raw materials etc.); to accommodate for population shifts; and to satisfy the needs of those who can't work such as children and the elderly etc. There is not technically any need to produce above and beyond this speaking purely theoretically. But capitalism cannot be satisfied with this. It has to constantly produce more, a surplus over and above what is actually needed or demanded. This surplus itself is the origin of wealth and capital accumulation. Without this, capitalism would largely cease to be!

But where does this extra surplus value go? That is the age-old question. And it was only answered by Marx. Marx determined that the portion of surplus value goes back into the production process to increase the overall output. That is to say, it is reinvested back into the production process. He determined the general formula of value as follows:

Value = constant capital + (variable capital + surplus value); or, c + v + s

Now, the portion of s’ is reinvested back into the production process, specifically to increase the amount of c and v. A portion is used to maintain the wear and tear of tools and machines. But a portion can also be used to upgrade or expand machinery if available. Moreover, a portion can be reinvested in v, which is the cost of labor, or that is, workers’ wages. This may be necessary, for example, when hiring more workers etc. along with expanded production. It could also be used for wage raises. But in this case, the organic composition of capital and the rate of surplus value must always be higher than v. Put simply, this means that the rate of “productivity” etc. must exceed the amount (re)invested in wages if a constant surplus is to be maintained. The figure for this simple reproduction of capital, the basis for capital accumulation, is as follows:

This is just simple reproduction. There is also enlarged reproduction of capital. Simply put, this means that total social capital increases and accumulates. The significance of this is that a surplus must always be maintained and then reinvested somewhere. The cycle of accumulation never ceases because, again, if it did so, it would also cease to be capitalism.

Rosa Luxemburg dealt in detail with capital accumulation. She wanted to know what happened to the extra surplus, the s, since it always exceeded demand. Who were the extra consumers and where did they come from? Her basic answer was that capitalism always needs to expand to find new markets, new forms of commodification, and to bring previously non-commodified or non-capitalistic goods etc. into the market. This could be done through colonization, warfare, privatizations, or other means. This would create new avenues for capital expansion. It would allow not only new places for investment, but also provide new access to raw materials and labor power. Both of these could be used to lower the costs of c (which includes raw materials) and v (labor power) and thus increase the rate and amount of s.

But there is a problem. Capital accumulation inherently leads to crisis and especially crisis of overaccumulation. This manifests itself in warfare, inflation, etc. First, there is the crisis of overaccumulation capital, or s, itself. When it runs into limits, it seeks to overcome them through forcefully creating new markets etc. Second, there is the crisis caused by the increasing organic composition of capital, or the ratio of c:v. As the production process becomes further mechanized, the costs of c become higher. At the same time, there is less need for large numbers of workers, so the cost of v gets lower. However, this results in a contradiction. This is because only workers’ labor power can create new surplus value. Machines and tools by themselves cannot create this. Capitalism can try to overcome this, again, by creating new markets and thus obtaining demand for more labor.

But what happens when it can’t? What happens in a low growth scenario and when capitalism has largely run out of places to expand into? Then there is a crisis of value creation. In this scenario, masses of workers are either out of work or working precarious jobs. They themselves are not creating much value. But the cost of goods and raw materials is expensive due to increased production costs and costs of running expensive machinery etc. There is also high demand for many of these goods, especially essential goods such as food, housing, and clothing. When people’s wages are no longer enough to cover the cost of living, such as for example purchasing a house, and capitalism can no longer create new value to compensate for this, then the use of credit and finance will inevitably expand. That is to say, for example, more people will take out loans to buy major purchases like homes and cars etc, and even microloans to purchase basic necessities.

The explosion of credit and finance therefore is a direct response to the crisis of value creation and capital accumulation and is in direct inverse proportion to the amount of new value creation. The overall scenario can be envisioned as follows:

Figure 1: A conception of inflation/deflation in relation to value creation and credit/finance.

© Justin Aukema

Growth rate here is bourgeois economics lingo but what I actually mean by it is the rate of surplus value, or the rate/amount of new value creation. When this is high, there will be little need for credit and finance schemes because, on the business side there is already enough rate of profit and surplus value to compensate for this, and on the consumer side, wages are either high enough to cover costs or costs and wages alike are both low in the first place. But as the amount of new value being created goes down, capitalists will need to cover their costs and obtain their profits through other means (credit) while consumers, too, will rely on credit to buy their goods.

This relates to inflation and deflation as well. High rates of profit and value creation are often linked to labor intensive and highly competitive commodity production scenarios where the cost of labor, machinery, and commodities are all very low. With little finance in the mix, this means there is generally a trend toward deflation resulting from a race-to-the-bottom commodity competition. But as value declines and credit expands, high demand, inability to purchase with anything other than credit, and high production costs from high constant capital, c, levels means that the price of basic goods will also go up. The capitalist must realize his surplus value through the completion of sale and compensate his costs and his hungry pockets somehow.

The overall element of crisis here can be explained simply as this: when credit increases and value creation decreases, there is more likelihood of crisis. This is obvious because credit itself is simply a promise of payment. But as value creation goes down there is actually less and less likelihood of that payment occurring in the first place. More and more people may be buying expensive homes etc. on credit, but if they are facing less stable income or decreased wages etc. then their ability to repay is threatened. In sum, this model confirms Marx’s thesis of crisis as the result of an inability of repayment.

Japan’s situation

Now, you might ask how Japan fits into this picture. Don’t they have massive deflation? What’s the deal? Well, actually Japan also fits this model perfectly. But it is not possible to understand Japan’s situation using traditional models for gauging inflation such as monetary theory or theories involving interest rates. After all, Japan has incredibly low interest rates and pioneered unconventional monetary policy through quantitative easing. So according to mainstream theory all of the factors are there. Except for the inflation.

Or so it seems. The basic point is that Japan uses massive amounts of credit and has very little value creation. Government debt has ballooned to 200x the country’s GDP. This is why interest rates must be so low: because otherwise the government couldn’t pay back the interest on all of its bonds. At the same time wages in Japan are incredibly depressed. This itself is a result of capital accumulation wherein the ratio of c:v steadily rises as explained above. This scenario increases the industrial reserve army of labor including the precariously employed who now make up 40% Japan’s workforce. It can also lead to increased production costs but also less ability to purchase basic goods. This gap thus must be made up for with credit.

As is indeed the case. The actual price of essential goods such as homes, for instance, is well beyond people’s actual purchasing power. Homes are especially important because they are in fact the inflation sink that rising costs are buried into. The expansion of credit through home loans makes up for this gap and with low interest rates it enables people to obtain their bare essentials while simultaneously maintaining the fiction that runaway inflation isn’t happening.

But this fiction is getting increasingly hard to maintain. This is because Japan also suffers a major lack of value creation. The country has experienced little to no new growth for the past three decades. Attempts to compensate for this have mainly been achieved by Japanese corporations moving production overseas to cut labor costs to their bare minimum. This also reduces some commodity costs in Japan which is itself necessary since Japanese workers’ own wages are insufficient to buy anything other than super cheap goods. This method of value creation may increase the rate of surplus value and capitalists profits. But ultimately it does not benefit Japanese workers since the ability to purchase some cheap commodities is both a direct cause of and consequence of the cheapened value of labor both at home and abroad. Moreover, this counteracting influence itself is still subject to the same crisis of overaccumulation wherein the organic composition of capital, c:v, rises as production is mechanized and “productivity” raised etc. Thus even Japan will not be able to avoid the pitfall of rising prices versus increasing inability to purchase commodities.

Indeed, this is what we have already been seeing for some time. Much data on Japan looks at year on year CPI index to arrive at the conclusion that Japan has a deflationary tendency. This is partly supported by the further “evidence” of low interest rates and low wages. It is generally recognized even among bourgeois economists that Japan’s low wages are a problem. But those same economists get confused when it comes to demand. Instead of wages stimulating demand, they frequently say that prices stimulate demand. But this is a logical conundrum since wages and prices are intimately connected (although not the only factor, obviously). One problem is that wages and prices both can still be low but can also rise relatively in the long term. This is precisely what the data reveals. Ueno Takeshi from the NLI Research Institute compiled data on OECD countries from 1995 to 2020 comparing price rises with wages. This shows that while in other countries wages have risen faster than prices, in Japan the opposite has been true: wages have risen more slowly relative to prices.

Figure 2: The rise in wages vs rise in prices, 1995 - 2020; Originally printed in the Tokyo Shimbun

This creates a major problem that is not explainable with many other traditional theories. Furthermore, it complicates the assumption that Japan is experiencing long term deflation. Instead, the truth is more complicated. There is a tendency toward overall inflation in the global market as evidenced by rising prices. Even Japan is not immune from this. It imports key raw materials etc. upon which whole domestic industries depend (e.g. for house building etc.). Moreover, rising labor costs abroad may also complicate Japan’s hitherto business model of exploiting cheap foreign labor. Thus it is more accurate to say that the biggest deflation Japan is experiencing is only in the realm of v, of workers’ wages. This is a direct consequence of the cheapening of labor due to the capital accumulation process. It is illustrated by my model and the models of other Marxist scholars explained here. But most bourgeois economics itself either does not recognize or obscures this facet.

Incidentally, we can add one more statement here. This is the reason for Japan’s low wages in the first place. Most of this relates to the overall cheapening of labor through the capital accumulation process; that is to say, the shift in the organic composition of capital away from v. Obviously this will lead to problems of value creation and crisis. But even from a standard economics perspective there are other clear reasons. One benefit for Japanese companies is that lower wages, along with a weak yen etc., make Japanese exports more beneficial in the global market. Japan’s exports as a percentage of its GDP have risen greatly since the 1970s. Actually, there was a break in this after the 1985 Plaza Accords and a rise in the price of the yen. But this has rebounded from the mid-1990s to reach its present levels of over 18%.

Figure 3: Japan’s foreign exports as a percentage of its overall GDP; Source: World Bank

Because of Japan’s advanced monopoly capital and its high organic composition of capital, it actually costs a lot to make high tech goods in Japan. So what can Japanese companies do? Naturally, the only remaining routes available to them are A) to reduce the costs of constant capital by obtaining cheaper raw material imports; B) obtaining cheaper labor costs abroad; and C) cheapening labor at home through mechanization, productivity advances etc. A) is not really an option anymore, so only B) and C) remain. A reliance on the export market and low wages domestically means that Japanese corporations seek to realize the value of their products mainly abroad in richer countries rather than at home. In other words, they target mostly foreign consumers in America, China, Europe etc. rather than in Japan.

Now, positing solutions to this problem is beyond the scope of this essay. The aim was rather only to present a new way of thinking about inflation and deflation. One major lesson we can learn from this in the case of Japan is that it is possible to have a situation that looks like deflation but where there is actual inflation that is simply hidden. Interest rates and monetary supply etc., the main indicators of inflation in mainstream economics, though, cannot explain this facet entirely. Instead, as I have suggested, Marxist crisis theory relating to the organic composition of capital and capital accumulation offers a much clearer picture. Only this, in other words, explains why it is possible to have both declining wages and rising prices. Based on this, the obvious conclusion that many left-leaning economists draw, therefore, is to raise wages which they think will stimulate domestic demand. Of course, raising wages is necessary for the betterment of the global working class. Yet it is also not totally incompatible with the capitalist model of growth and accumulation. Indeed, capitalists must raise wages to a certain extent (enough to buy basic necessities) to support the reproduction of the working class. In addition, capitalists can generally raise wages insofar as this rise itself doesn't threaten the portion of surplus value, s, being extracted. This can be offset with rises in and exploitation or so-called productivity. Or, another option available to capitalists is to continue to depress wages and instead to make up for rising prices with the expansion of credit. Finally, another more extreme option would be to resort to other measures such as locking down a portion of the global working class in order to shut off or to regulate global supply and demand. This is especially important in times of crisis when a large portion of the working class becomes redundant (surplus population); in times of looming hyperinflation due to ballooning prices and an inability to sell these goods; or when wage rises threaten the capitalists’ portion of surplus value. Indeed, some have argued that this was part of the purpose of the global Covid lockdowns in the first place.